In early spring many of the Midwestern woodland wildflowers bloom before the trees (mostly oaks) fully leaf out and create a shady canopy. There are also a few garden perennials from other parts of the world that bring color in to the early May garden. Let’s take a look a few that are at their peak of bloom right now.

In early spring many of the Midwestern woodland wildflowers bloom before the trees (mostly oaks) fully leaf out and create a shady canopy. There are also a few garden perennials from other parts of the world that bring color in to the early May garden. Let’s take a look a few that are at their peak of bloom right now.

In the picture above, common violets intermingle with Jacob’s Ladder (Polemonium reptans). Violets come in many shade of blue and purple, as well as yellow and bicolor blue and white. The violets above were propagated from a naturally occurring population that had reddish purple coloration (difficult to capture in an image) that complements many other early bloomers, including Ruby Epimedium (Epimedium x rubrum), seen below.

The leaves emerge a bright chartreuse green on the Ruby Epimedium – planted where the morning sun highlights this stunning color. The leaves turn a more standard green as they mature. Epimedium sulfureum, a similar species, flowers in yellow but does not seem to be as robust. At a foot or so tall and wide, epimedium works well in part shade in groupings of five to nine (or more) interplanted with other perennials.

Trilliums, such at the White Trillium (T. grandiflorum) seen below, are often collected from the wild and sold in garden centers, there are, however, some ethical nurseries that propagate their plants from seed or divisions – easy to do, and should be purchased from those sources. Timing is critical when collecting the seed, generally eight weeks past flowering, since the pods will eventually shatter and the seeds will drop to the ground – as long as the seeds are turning brown, they can be collected and planted in seed flats to expand a population of plants.

Trillium plants will fade after flowering and go dormant until reemerging the following spring, therefore it is best to plant them where the soil will not be disturbed – such as near the base of trees or large rocks. Other native woodland plants such as Hepatica, seen below, actually send out their new leaves for the season right after flowering, and look great all summer, and stay green through the winter season, only fading the following spring. Flowers, which range in color from pink, to white, to purpley blue, sometimes emerge as snow is still on the ground in late April.

Rue Anemone, like hepatica, is a member of the short flowing buttercup family. The flowers are pure white to slightly pink, with blue green leaves that remain throughout the summer if the soil does not dry out for an extended period. Rue Anemone looks great tucked into nooks and crannies throughout the shade garden. Leaves turn yellow in the fall months.

- Rue Anemone, Anemone thalictroides aka, Thalictrum thalictroides.

Lenten Rose (Helleborus sp.) is native to Europe and blooms along with the native woodland flowers. The large, coarse flowers can be an interesting complement to the other finer textured flowers in the shade garden. These easy to grow perennials can be divided after flowering, by cutting apart divisions with a bread knife, to create more plants.

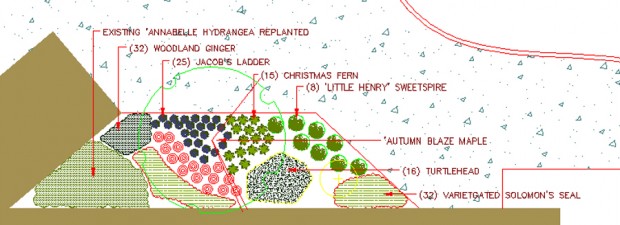

The low groundcover Sweet Woodruff (Galium odoratum) is widely found growing in moist woods throughout Europe and Asia, it also mixes well with our Midwestern natives as seen below with Woodland Ginger (Asarum canadense). The leaves of both the Woodland Ginger and the Sweetwoodruff wil stay green all summer if the soil is kept moist during dry spells.

Wood Shield Fern (Dryopteris marginalis) and Christmas Fern (Polystichum achrosticoides) are two easy to grow evergreen ferns native to the Midwestern woods. Wood Shield Fern’s, upright vase shaped growth, can reach two feet tall, while the Christmas Fern is more low spreading. Below both are seen mixing well with Woodland Ginger (Asarum canadense), Wild Ramp (Allium tricoccum), and Woodland Geranium (Geranium maculatum) with its pink flowers just coming into bloom in Mid-May.

Jacob’s Ladder (Polemonium reptans) is a neat low mounded woodland plant covered in sky blue flowers for a week, or so, in May. The rest of the summer, the pinnate foliage looks great and work well, planted along the edge of the shade garden as a nice transition to lawn or other pathway materials. The Jacob’s ladder often found in garden centers is a taller European variety, with variegated foliage – inferior in appearance to our Midwestern plants.

Blue Wood Phlox can be found blooming at the same time as Jacob’s Ladder, and slightly after Jacob’s Ladder is finished blooming. In May wiry flower stems shoot up a foot above the low evergreen foliage and put on a bright blue display that works well with other more sun tolerant Dutch bulbs such as Grape Hyacinth (Muscari sp.) and Tulips.  A mix of blues and whites in a rock garden I constructed at my home, gets plenty of sun in the spring, but is somewhat shaded by the overhanging Silver Maple in the summer:

A mix of blues and whites in a rock garden I constructed at my home, gets plenty of sun in the spring, but is somewhat shaded by the overhanging Silver Maple in the summer:

In one part of the rock garden, the shade tolerant Sedum ternatum, native to Midwestern woods and limestone bluffs is just starting to put out its white, star shaped flowers. The sedum stays evergreen the year around and works well as a groundcover in the shade garden.

In one part of the rock garden, the shade tolerant Sedum ternatum, native to Midwestern woods and limestone bluffs is just starting to put out its white, star shaped flowers. The sedum stays evergreen the year around and works well as a groundcover in the shade garden.

Most sedums, this one included, can be propagated by pinching off a short stem and pushing the base of the stem into the ground where more plants are desired. Occasional watering of the cuttings will promote quicker rooting.

Virginia Bluebells (Mertensia virginica) is such a ubiquitous old fashioned perennial, that many gardeners are unaware that it also is a American woodland native – mostly found in flood plains, but very adaptable to well drained garden soils. The charming bell-shaped blue flowers only last a week, then the plants begin to wane, turn yellow, and go dormant for the summer, it is therefore a good idea to note where these plants occur, so that the plants are not inadvertently disturbed while gardening in the summer months. Interplanting Virginia Bluebells with others perennials that will help mask the fading foliage is something to consider as well. Virginia Bluebells can form large colonies by dropping its seeds in bare soil surrounding the mother plant, these volunteers are easily removed if desired. The roots are fleshy and can be divided after the plants are finished blooming to create more plants. Virginia Bluebells will do well in most decent garden soils.

Virginia Bluebells can form large colonies by dropping its seeds in bare soil surrounding the mother plant, these volunteers are easily removed if desired. The roots are fleshy and can be divided after the plants are finished blooming to create more plants. Virginia Bluebells will do well in most decent garden soils.

A mass of Virginia Bluebells overtake the low evergreens when in bloom, only to quickly retreat with equal vigor

Another early blooming European native is the old fashioned Money Plant (Lunaria annua.) Grown for the silver dollar sized papery seed pods (silicles) that are used in dried arrangements. This plant will reseed around the mother plant, and in some soil types this may be a nuisance. In my experience, the mother plants have survived many winters (unlike what the name implies) to rebloom in the spring and provided more dried arrangement material the following fall.

For a punch of bright orange in May, Trollius europaeus, or Globeflower, cannot be beat. The plant, hailing from Europe, prefers a bit of shade and consistently moist soil but otherwise is a rather carefree perennial. It blooms at the same time as some of the Giant Purple Alliums and Chives and the purplely pinks allium blooms could make for an interesting combination with the bright orange blooms of the Trollius.

Lastly, we get back to some Midwestern natives for the shade. Many sedges do well in dry shade, Penn Sedge (Carex Pensylvanica) being one of them. This sedge is one of the “sod” formers, as opposed to forming neat tufted “clumps.” Use this growth habit to your advantage by interplanting such shade plants as the trilliums, noted earlier, violets, whose electric blue flowers play well with the bright green foliage of the Penn Sedge.

Lastly, we get back to some Midwestern natives for the shade. Many sedges do well in dry shade, Penn Sedge (Carex Pensylvanica) being one of them. This sedge is one of the “sod” formers, as opposed to forming neat tufted “clumps.” Use this growth habit to your advantage by interplanting such shade plants as the trilliums, noted earlier, violets, whose electric blue flowers play well with the bright green foliage of the Penn Sedge.

The flowers of the Penn Sedge are a bit underwhelming, but the yellow anthers can sometimes be considered a bit showy in mass plantings.

Penn Sedge spikelet – not showing yellow anthers in this photo – few seeds, seen in front of lower finger, are produced and are difficult to collect, as they drop immediately when ripe

All Violets (Viola palmata shown below) look great interplanted with other woodland plants, especially Penn Sedge.

As do specimen plants such as Jack-in-the-Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum). While the plant itself goes dormant after bloom, a showy red seed mass forms to catch the viewers attention in late summer, very cool:

Or Sessile Bellwort (Uvularia sessilfolia) whose foliage looks good througout the summer. The dainty pendulous yellow flowers are curious, if not overly showy.

Or Sessile Bellwort (Uvularia sessilfolia) whose foliage looks good througout the summer. The dainty pendulous yellow flowers are curious, if not overly showy.

These are just some of the interesting plants that come into flower early and can be combined with each other and with later flowering plants to great effect.