Midwest native trees, shrubs, wildflowers, and grasses were available at the plant sale.

The landscape beds around the district headquarters contained an interesting mix of prairie plants and trees. Shown here are Baptisia australis, or Blue Prairie Indigo, in flower

Connor Shaw gave an informal presentation at this spring's inaugural Will County Forest Preserve's native plant sale on June 1st, 2013. Owner of Possibility Place Nursery, in Monee, Illinois, Connor grows Midwest native trees, shrubs, wildflowers, and grasses.

In his presentation, Connor touched on how to properly plant a tree, the best time(s) to plant, and how to care for the tree after planting.

For field grown trees, otherwise known as balled and burlapped (or, B&B), he suggested that the best time to plant is early spring (March and April) or after the month of July, up until the ground freezes solid in the fall. Connor also stated that "August is the best time to plant anything, roots can grow 24 inches by the first freeze." Evergreens were the exception: "Plant those in July, the candles (new branch growth) are grown out by then."

Connor Shaw, with a young oak from his nursery set on the table behind him. Note the shape of the pot. These stepped pots with small, 5/64" holes along the ridges help to prevent circling roots.

Connor expressed that, if planting more than one tree, the spacing between trees can vary from one foot to 25 feet or more. Multiple trees can be planted in the same planting hole to form a “clump” or multi-stemmed tree.

Overhead obstructions, including power lines need to be noted and the mature spread of a tree’s crown should be taken into account, when determining a planting location.

Holding a #5 pot (a pot which holds approximately five gallons of soil), containing a three foot tall Bur Oak, Connor explained how choosing to plant that young oak is most often a better choice for homeowners, than a tree three times its size. Simply stated, larger trees require a longer period of after care. As a general rule, it takes a tree one year to reestablish its root system for every inch of trunk caliper. Therefore, a tree with a three inch caliper is going to require hand watering once a week for three growing seasons, for any week that there is less than one inch of rainfall. So that young Bur Oak will only need to be hand watered during its first summer. Or, Connor assured the audience, if the oak in the #5 pot is planted between September 15th and October 15th, it can be watered once at planting time, then forgotten, as far as hand watering goes.

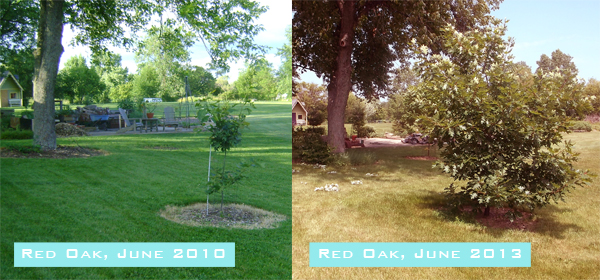

An oak, once established, will typically grow two feet a year, in Connor’s experience. I commonly have observed oaks that have grown as much as that and more in a season. Oaks tend to push out new growth throughout the summer, as long as they are happy. Connor noted, that while the larger caliper oak will be occupied with establishing its root system for several years (since most of its roots were lost, when it was dug from the field), the container grown oak (which had 100% percent of its roots from day one) will soon surpass it in height within three or four years. Planting smaller trees is definitely the way to go, at least in a home landscape. A street parkway, or other high pedestrian traffic public space may require that larger trees be installed due to other considerations

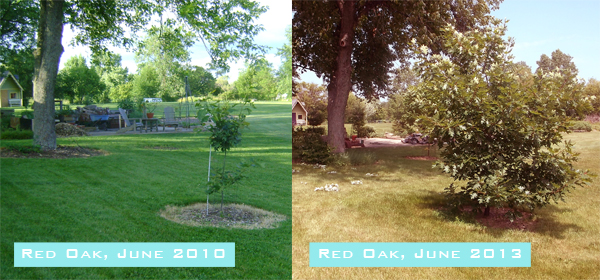

A young oak (in my backyard) shows the amount of growth possible in just a three year period. Also note the trunk girth at the soil line in the current picture, compared to 2010. Leaving the lower branches on the tree also allows for faster growth, overall.

Finally Conner noted the importance of applying wood mulch, a few inches deep, around newly planted trees. This helps to keep moisture in the soil and weed growth down, reducing the chance of mower or weed trimmer damage to the delicate bark. The mulch should most definitely not be built up to form a “volcano” around the base of the tree, and in fact, it should be kept from coming into contact with the bark of the tree. In addition, he strongly suggested protecting the trunks of newly planted trees with chicken wire to keep gnawing animals at bay, including beaver, explaining how he lost several newly planted River Birch, the first night after planting, to these critters. To add to that, I would (and do) surround any young tree with four foot high wire fencing where deer are present and would likely eat the tree buds in winter and new spring growth. Deer also seem to like to rub their antlers on the trunks of young trees, doing a great deal of damage in the process by way of girdling the tree and ripping off branches. This wire fencing will protect the tree from this damage.

Connor's years of experience in growing a wide variety of plants was in evidence as he offered insight on what to pay attention to when planting trees, how best to approach the idea, and finally how a little care and protection goes a long way to getting the trees on a good start to a long life of providing shade, beauty, and habitat for wildlife.